As you recall, Jenny Vidbel is the animal trainer of the Big Apple Circus — which is coming back to town! Below is a transcript of the second segment of our recent interview. Read on to learn:

As you recall, Jenny Vidbel is the animal trainer of the Big Apple Circus — which is coming back to town! Below is a transcript of the second segment of our recent interview. Read on to learn:

* how Jenny’s parents would have threatened her as a teenager

* about the peace she experiences at work, and

* what she hopes to be doing fifty(!) years from now.

So, you were a teenager. With rebellion?

JV: No, we were on a circus, my grandpa’s circus, and we moved every day. We were in a different city every day, and there’s a lot of work. My sister and I had our jobs that we did, and it was with animals. We had a petting zoo that we would set up. We’d care for the animals, feed and water and clean them and do all that. So there was rebellion? No, there was just no time for it.

HC: You didn’t say “I’m not going to be in the circus, I’m going to be a lawyer!”

JV: No.

HC: To upset your parents.

JV: I think if they wanted to threaten us, they would say we were going to go home. And you know, go to public school and live a normal life. That was the threat for us. (Laughter)

HC: I remember you mentioned that your parents were very supportive – if you wanted to be a dancer, whatever you wanted in your life, to stay home, they were supportive, so there wasn’t anything to rebel against?

JV: There really wasn’t.

HC: In your upbringing.

JV. Yeah.

HC: So you were able to focus, and develop your love for the animals.

JV: Yes, absolutely. My sister went a different route; she wanted to be an aerialist, so that’s what she did. My grandparents were not thrilled with that because there’s danger, a great deal of danger involved. But they supported her, and she’s an accomplished aerialist.

HC: Aerialist, not acrobat.

JV: No

HC: There’s a difference.

JV: Yeah, acrobats are on the ground. Aerialists are in the air.

HC: Not a trapeze artist?

JV: A trapeze artist is an aerialist.

HC: Is a kind of aerialist.

JV: Yeah.

HC: So this is something we learn as well, the differences of artists within the circus. Tell us more!

JV: When I was 12, my sister wanted to do aerial – when we were 12, we’re twins – I loved my grandfather’s little white ponies, I just adored them. And he had eight of them. I knew that’s what I wanted to do. I started out with one, and my herd just kept growing. As I got more experienced and really started learning about horses, that’s what I wanted to do.

HC: Looking back, a 12 year old knows things, also a 12 year old does not know a lot. As a 12 year old – I hear you say it with such certainty – how did you know? What indication did you have of your certain knowledge of what you wanted?

JV: I was around my grandfather my entire childhood. He had this great love for animals, and that’s where he spent his time. He was in the barn, with his animals, all day. He would do his last barn check at midnight, and he was up at six in the morning to be right back down there again with them. I followed him, that’s where I wanted to be. There was just no question. And it wasn’t really even a thought; I didn’t have this goal, or this idea that this is what I was going to do. It was what I was doing. And I loved it. I didn’t want to be anywhere else.

I was home schooled, my grandmother was our teacher and I just could not wait to get out of the house. I was a very good student because of that. We couldn’t leave, my grandmother was very strict with the school. We got up in the morning and we could not leave the house until we were finished with our lessons for the day. So I was quick. I’ll read, I’ll do whatever you want me to do. Please I want to go to the barn, please. So it was great motivation, I just wanted to be in the barn around all those animals.

And to be around my grandfather who had this love. I wanted that too. I wanted his passion and love for what he did. He was so happy no matter what, and here I am doing the same thing. You would see my grandfather in the pouring rain trying to fix a tent, or a flat tire or whatever because it’s part of the business. Not only setting up and tearing down the tents and stables, but the in-between, the traveling. When you’re carrying a lot of animals in a trailer, you might get a flat tire, you might break down. But you do everything with joy. This is what we do and we love it.

HC: You talk about work almost like it’s the air you breathe.

JV: It is. It’s the hardest thing to explain. When people talk to me about my job, I say it’s not a job. It’s so far from a job. I’m doing what I love to do and I get paid for it and that’s amazing to me — that I can make a living out of this. It’s kind of like a hobby or it’s my passion that I’ve made into my career. It’s great.

HC: Congratulations on finding this, and living it, and thriving, so clearly. How do you know when you’ve done a good job?

JV: In whatever I do, if I’m starting a new project, there’s just kind of a peace that comes over me. If I’m unsettled in something, then I’ll slow way down and I’ll think I’m not going in the right direction. It has to feel 100% right. I think I’ve really succeeded when I’ll have these questions and I back right off and I look kind of to a higher power and go with what feels really peaceful. Sometimes it means just waiting, waiting for the right answer. And I will, and it always turns out perfectly. Not the way maybe I had planned, I had these ideas and if they don’t feel right I quickly back off. In the end, here I am at Big Apple Circus where I’ve wanted to be my entire life.

HC: Is that right?

JV: Yes.

HC: I want to get to that. “It turns out perfectly.” I heard you saying. And what I understood following that, is “perfectly as it was, perfectly as it is.” You have an acceptance, and so it is perfect, as it is.

JV: As it is. It wasn’t maybe the plan that I had, but this is far better than I could have dreamt up. I just went with it instead of being stuck to this path, this idea. I just went this other way and it turned out just beautiful.

HC: So Jenny is describing a kind of barometer of sorts, inside, that you pay attention to, that lets you know how you’re doing, guides you in some ways. I think a lot of people at work get sort of cloudy, that barometer, that internal measurement gets foggy, it’s hard to pay attention to. You relate such clarity in being guided by what you have inside.

JV: Yeah, and It’s a funny thing to try and explain. But you really need to have peace. You need to have peace about where you’re going. You don’t have to have clarity, but you have to have peace.

HC: What does that mean, “peace?” Read more →

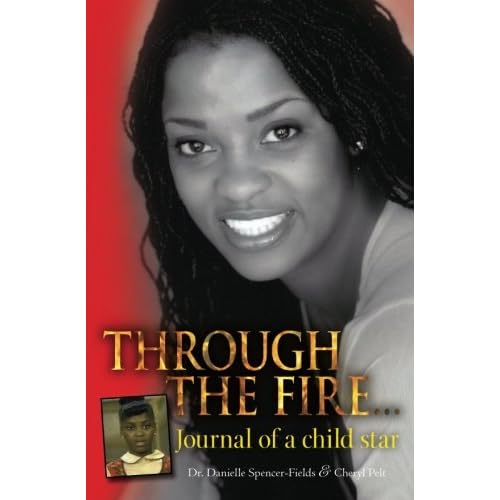

One of our most adored TV shows growing up was What’s Happening!! starring Danielle Spencer as Dee Thomas. To us she was the main attraction, with dialogue that made us chuckle. To wit:

One of our most adored TV shows growing up was What’s Happening!! starring Danielle Spencer as Dee Thomas. To us she was the main attraction, with dialogue that made us chuckle. To wit: Contrary to his teddy bear looks, pioneering scientist

Contrary to his teddy bear looks, pioneering scientist